The summary

Why facts don't form beliefs

Everyone wants the summary.

But the summary is what’s left after someone else decided what matters.

Their priorities aren’t yours. Their filters aren’t yours.

When you operate on summaries, you’re thinking with someone else’s brain.

Reflect on how much of your media consumption is fleeting.

Sixty-second reels, three-sentence social media posts, two-minute newsletters; most of what comes across our desk is designed for convenience.

You can argue whether the media has conformed to our short attention spans or vice versa. It’s a chicken-and-egg, and in fact, there is no real reason to spend time debating this.

It’s much more important to recognize how we (and others) create beliefs.

The popular belief isn’t always the correct one. Nor do facts form beliefs.

Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman encapsulates this in his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow.”

“I believe in climate change,” Kahneman writes. “I believe in the people who tell me there is climate change. The people who don’t believe in climate change believe in other people.”

In other words, most people who have strong feelings about climate change don’t have data to argue one way or the other. They are more than likely regurgitating summaries they adopted from other people. People they trust.

This is how we form most beliefs. We don’t examine evidence to reach conclusions. We trust people, listen to them, and adopt their views.

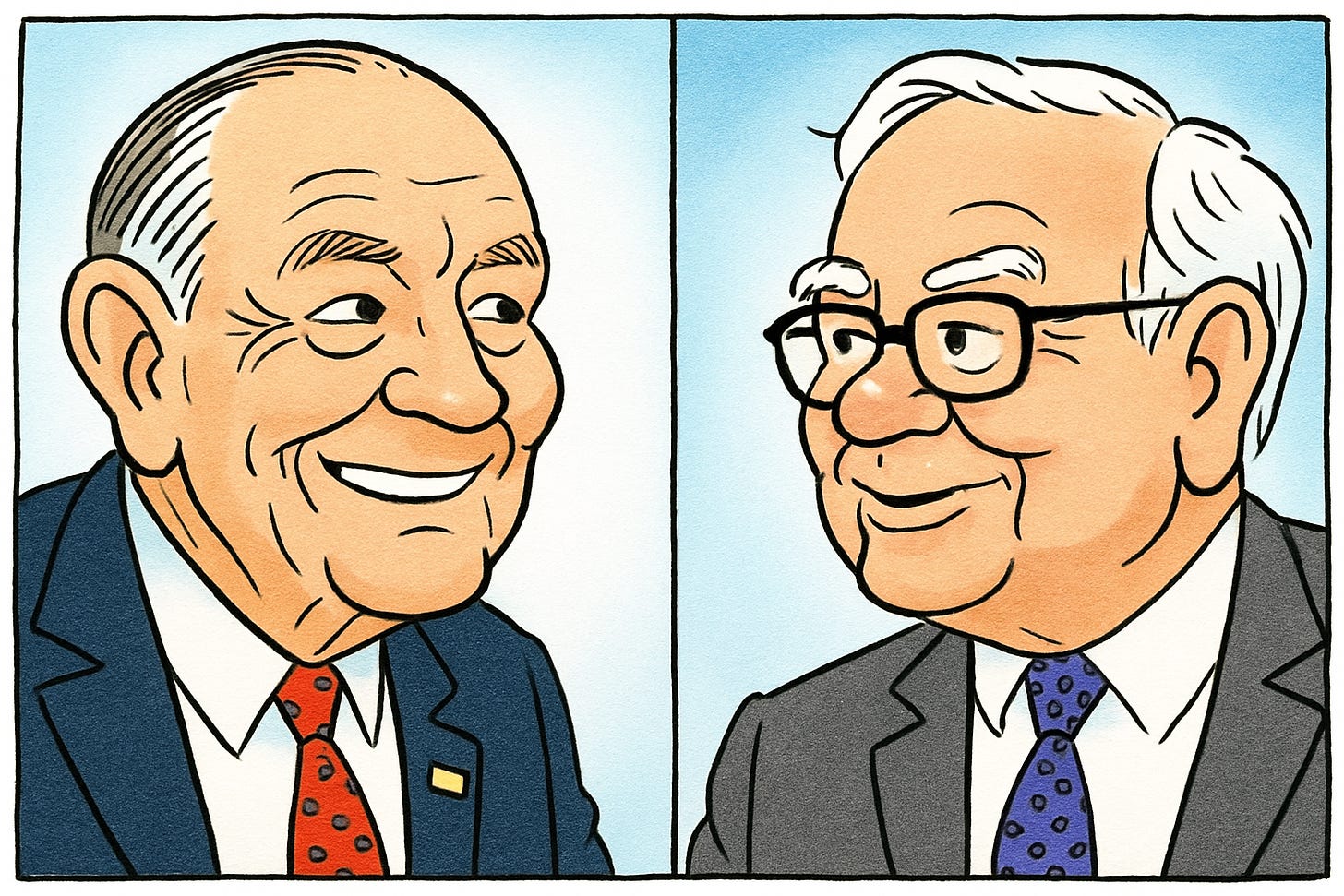

As Vanguard founder John Bogle noted in a 2000 speech to the Sunday Breakfast Club of Philadelphia, “I hardly need to warn you that the fact that Mr. Bogle and Mr. [Warren] Buffett agree doesn’t prove anything.”

One of the most influential financial minds of the 20th century has the wherewithal to admit that just because he and Buffett have a belief backed with empirical data and 100+ years of combined experience, it does not mean it will come to fruition.

Yet, after hearing one podcast, watching one TikTok, or reading one article, you believe you know all truths.

It’s important to recognize that reason is rarely the cause of our beliefs; it’s the stories we tell ourselves afterward that lead to how we compartmentalize our beliefs.

Even if you do present facts regarding a topic to a dissenting party, they are unlikely to adopt your view.

Rarely (and unfortunately) do people enter a conversation or consume media with an open mind. If they trust you (or the media member), they’ll find reasons to agree. If they dislike you/the media member, even the best evidence won’t change their mind.

As Shane Parrish writes, “Smart people hold different beliefs because they trust other people.”

This is not an essay aimed at shaming your media consumption or beliefs. Rather, it’s meant to be thought-provoking regarding how you create your beliefs.

Are you being controlled, a victim of the ease of summarization? How often do you challenge your own beliefs? Dive deeper into a topic?

Remember, you don’t need an opinion on everything.

Make your beliefs count.

“The path of least resistance and least trouble is a mental rut already made. It requires troublesome work to undertake the alteration of old belief.” — John Dewey

Early on in my career, one of my mentors told me to become an expert at something. You make yourself valuable and possibly indispensable especially if you become quite knowledgeable about something that not everyone in your field knows much about.